By Susan Lutz

One week coffee gets a bad wrap, the next a good one. Which is it? Is coffee good for us? Killing us? Destroying the environment? Causing cancer? Delightfully tasty? Or all of the above? From the deep grind of espresso to the convenient, light fair of the K-Cup, we love it. However, are we taking care of the earth and the growers as we sip down our brew and satiate that morning, afternoon, and even evening desire?

One day with a few minutes to spare on an errand run, I stopped in Dunkin’ Donuts. When I was growing up, the brand stood for doughnuts – lots of them. It was a sinful, delightful treat and soon became a sign of too much. Yet, Dunkin’s found a way to turn the focus more on coffee and a bit less on the doughnut part. In part, getting a sugary latte-something will replace a hole a doughnut is waiting to fill. When I approached the door, I saw a Fair Trade sticker on a poster advertising that Dunkin’ Donuts buys Fair Trade beans for espresso. I was thrilled to get my double espresso over ice knowing it was Fair Trade. The joy goes down a notch when I’m handed the disposable cup – a glitch in all take-out facilities. The cup I received wasn’t Styrofoam, though I know Dunkin’ was famous for those white cups. NYC banned Styrofoam take-out containers. Dunkin’ says it’s working on phasing out the material all together.

On the other side of the block, Starbucks takes on the same issues: the material of the take-out cups, the origin of the coffee, and the treatment of the people who grow and pick the beans. Starbucks purchases from Fairtrade International and other sources, including the company’s own Coffee and Farmer Equity Program called Ethically Sourcing. Starbucks claims 95% of their coffee is ethically sourced:

The cornerstone of our approach is Coffee and Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E.) Practices, one of the coffee industry’s first set of sustainability standards, verified by third-party experts. Developed in collaboration with Conservation International (CI), C.A.F.E. Practices has helped us create a long-term supply of high-quality coffee and positively impact the lives and livelihoods of coffee farmers and their communities.

On the other side of taste and quality comes the K-Cup. Sales tripled just a few years ago. The convenient one-cup brewer tripled, making an increase of over 200% and over 31 billion in sales in 2011. Perhaps campaigns to kill the small plastic cups with just a one-time use put a dent in sales.

Today, the outlook looks a bit bleaker for the convent cup. Holiday sales reported a sixth straight quarter loss in sales by Keurig. The sale of the little cups is down too. Consumers are heading back to the barista and other traditional ways to make coffee. The first time I saw one of these machines, a natural “yuck” look came across my face like I’d just sucked on a lemon. Instinctively, I imagined that all that plastic making one little watery cup of coffee was just a bad idea. Today, I notice the machines pushed further back into the corners of offices, the dying K-Cup tossed asunder, forgotten, and ignored. Keurig’s slow response to changing the plastic cups into something recyclable by 2020 must not have sat well with coffee drinkers. Really? 2020? (Read my article on The Many Shades of Green for more information). The consumer has spoken.

This year, the Dietary Guidelines for the U.S. looked at coffee and health. They concluded that coffee was part of a “healthy lifestyle.” Not just one or two cups of coffee but up to five.

“Strong and consistent evidence shows that consumption of coffee within the moderate range…is not associated with increased risk of major chronic diseases.”

Eating five celery sticks is healthy; five glasses of water is great, but five cups of coffee? Studies like this succumb to our coffee desires. We will continue to get reports about the good and the bad of coffee. I’m waiting for more studies to look at the high level of pesticides used to grow the crop and the effect this has on workers and consumers.

Though sales go up and down, the desire grows and the consumers of coffee get younger. I watch kids order from coffee houses with ease and authority. They sit at tables with a steamy cup of joe. Coffee hooks us with the smooth image of connection. At the coffee house, neighborhood store, coffee machine in the corner, we’re drawn towards getting along for that sweet amount of time it takes to brew a cup of coffee.

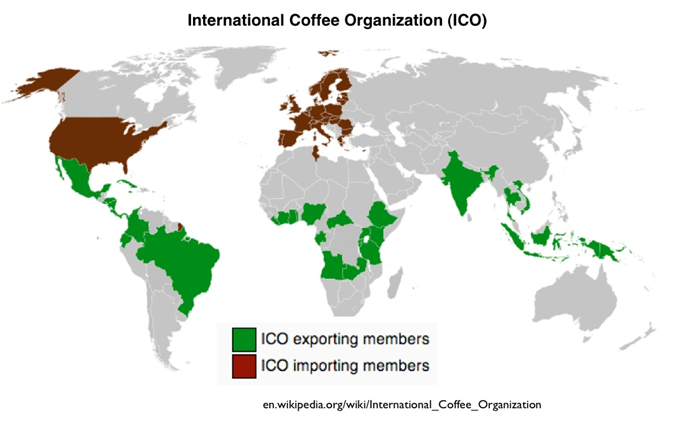

Commodities inherently demand we get along on a global scale. We can’t drink, eat, and wear things when we have no idea where they came from. We can’t ignore the people planting and picking the crop. A simple map quickly shows who wants the coffee and who grows it.

Commodities inherently demand we get along on a global scale. We can’t drink, eat, and wear things when we have no idea where they came from. We can’t ignore the people planting and picking the crop. A simple map quickly shows who wants the coffee and who grows it.

We can no longer take for granted whether or not a product is good for us, environmentally sound, and treats the farms well just because it’s packaged well or the latest scientific study says it’s healthy. We’re smarter than that. We have the power to demand more from the giants who sell us our daily grind.